Drawing a line in the sand - a history of drawings in architecture

- IH Architects

- Feb 20

- 5 min read

Drawing shapes— and are shaped by—architecture but faces an uncertain future.

By Ar. Ihsan Hassan

This essay on the history of drawings in architecture accompanies the exhibition "Kebuk Semaian" at Rumah Lukis gallery, which showcases a diverse collection of drawings and sketches by architects, artists, and individuals from non-creative fields. The exhibition highlights the varied ways in which drawing serves as a tool for thinking, recording, and processing information. For further details, please visit: https://www.instagram.com/reel/DFS7wV0z_h-/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Drawing is often seen as an eternal pillar of the architectural discipline—a timeless practice linking past, present, and future. But this perception isn’t entirely accurate. Drawing, as we understand it today, is not some ageless, unchanging tool of design. In fact, its role in architectural practice has evolved over the centuries, reflecting shifts in culture, technology, and the very nature of design itself.

Let’s start by debunking a common myth: the idea that great architecture has always been based on drawings. Gothic cathedrals of medieval Europe, for example, were largely constructed without the kind of technical drawings we rely on today. Instead, their creation was guided by oral traditions, proportional systems, and hands-on craftsmanship passed down through generations. Some prefer to call this the Engineering Method, where rules of thumb form the basis for structural geometry, later blossoming into ornamentalised structures. It still baffles modern-day observers today that for such complex structures, drawings played a secondary role in the design and construction of Gothic cathedrals.

When such memory faded and craft knowledge was lost, drawing is often used as a tool to recover lost knowledge. By the 19th century, architects in Europe have already forgotten the trade secrets of the mason guilds leading architect Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) to produce drawings that rediscover how Gothic vaults were assembled and the remarkable efficiency of its structural system. It still fascinates people to know that much of the final execution of Gothic architecture was left to the expertise of craftsmen on-site.

Drawings became increasingly embedded in building construction as a sociological shift occurred, beginning from the rise of European Enlightenment. The early modern period saw drawings shaping architectural knowledge and gaining its pole position as a medium of communication. The growing centrality of drawing as a tool marked a shift of power from oral and material traditions to a more scientific and legalistic profession. The first architectural academy, École des Beaux-Arts in France, began its drawing-based vocational programme as early as the 17th century. This pedagogical method spreads across the globe through a complex process of mutual exchange and colonial imposition. It still forms the foundation of many contemporary architectural education across the world. Within this convention, drawings are used to teach grammar, brainstorm and debate ideas, and communicate them to an audience familiar with the rules of drawing.

As colonisation spread, European Enlightenment culture and the use of drawings became well-established as mediums of communication and knowledge in Asia. Drawings by colonial subjects, such as by some of the earliest professional Architects in Malaya, such as R.T. Rajoo (1915) and Tomlinson & Tian Fook in the 1930s, exemplify the dominance of Western culture and drawing as the unrivalled basis of the architectural culture, slowly replacing the oral-based indigenous building traditions of Asia.

By the mid-20th century, during the upheavals in Europe, as well as the rise of independence movements across Asia and Africa, a new spirit emerged. A collection of aesthetic, philosophical, and artistic ideas, later termed Postmodernism, began to disseminate across intellectual culture. Postmodernism reacted against the rigid, oversimplified, and ideological frameworks of Modern ideas that was rooted in rational, industrial, and scientific culture. Instead, Postmodernism celebrated redefinition, revision, and experimentation. It privileged the everyday over universal metanarratives, rejecting conventions and celebrating novelty. Today’s intense political debate on gender and pronouns for example is a result of this same cultural phenomenon that began in the 1960s.

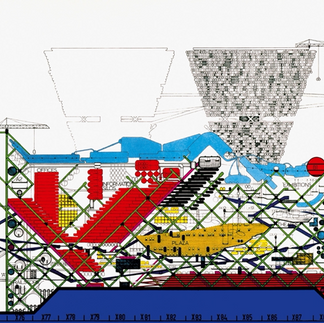

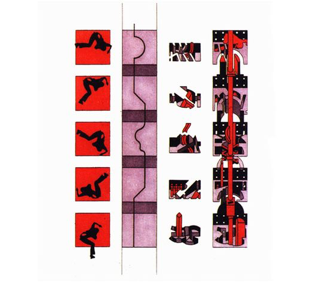

In this era of flux, architectural drawings took on a more philosophical and experimental shift. Consider the influential works of Peter Cook, which inspired generations of architects, or Zaha Hadid’s spectacular competition entry for The Peaks; or Bernard Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcripts. The use of drawing to explore architecture through new lenses – experiential, geological, technological, ideological – became dominant among architects. These works demonstrate that drawing is no mere tool for communication—it has become an integral part of discourse and hypothesis. Even for a solid Traditionalist such as Leon Krier, drawings are not mere studio tool of the Beaux-Arts – it was an act of rebellion against the Modernist architectural culture. As societies industrialised and embraced digitisation, drawings evolved into an elevated discursive medium becoming closer to objects of art.

![In his own words, Bernard Tschumi’s Manhattan Transcripts (1981) “differ from […] architectural drawings” but are meant to “transcribe […] interpretation of reality”. These drawings are not of buildings specifically but of narratives of human experiences as they move within the urban space.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/c0a02f_1be34afb626a4baeadde76a7de144200~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_421,h_282,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/c0a02f_1be34afb626a4baeadde76a7de144200~mv2.png)

As the world transforms, drawings once again face a shift in their role within architectural practice. Computer-aided design (CAD), once seen as revolutionary, is now increasingly considered obsolete. Software such as Grasshopper and Revit are changing how buildings are designed. In these systems, designers essentially “write” buildings through algorithms that generate 3D model of the design. Hundreds of apps are appearing nowadays providing tools that can generate the most efficient parking layout, or create apartment floor plans by maximising density and zoning rules – with ability to produce outputs within seconds. As these tools grow more complex and achieve self-learning abilities, they could design and construct buildings entirely autonomously. In this paradigm, drawings become mere by-products of written programmes. In fact, there are already many architecture schools which have integrated such automation and robotics into their studio programme.

The exhibition today showcases sketches and drawings from architects and artists, capturing a slice of a society of practitioners in a midst of an intellectual and technological transformation. We may be living in the Golden Age of drawings, as the last generation of drawing-based architects continues to persist in using this medium of practice. For now, drawings remain a primary tool for discourse and practice—whether debating finer points of architecture, recording studies of buildings, legalising projects for local authorities, or communicating instructions to builders. The question is: for how much longer?

Comments